- LP

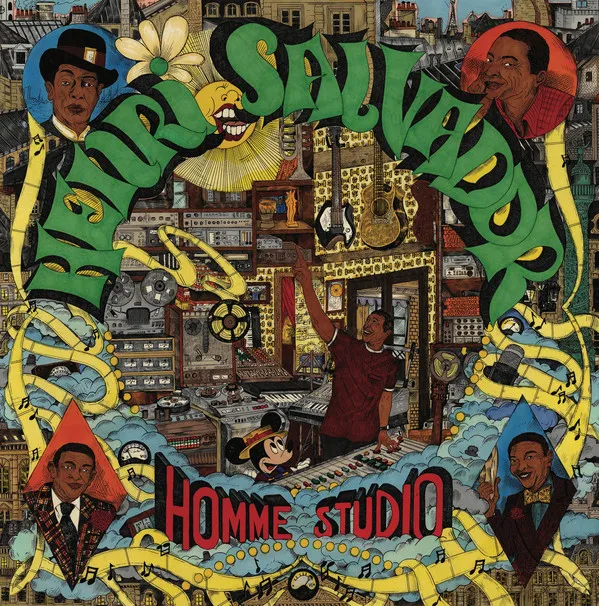

Henri Salvador

Homme Studio

Born Bad Records

- Cat No: BB141

- updated:2021-07-26

Track List

-

A1. Thème Du Bateau

1:47 -

A2. Siffler En Travaillant

2:23 -

A3. Et Des Mandolines

2:14 -

A4. L'Amour, Va, Ça Va

2:34 -

A5. Kissinger Le Duc Tho

3:12 -

A6. J'Aime Tes Genoux

3:30 -

A7. Sex Man

2:08 -

A8. On N'Est Plus Chez Nous

2:29 -

B1. Hello Mickey

2:41 -

B2. Pauvre Jésus Christ

3:10 -

B3. Le Bilan

3:09 -

B4. Marjorie

2:17 -

B5. Le Temps Des Cons

2:56 -

B6. Rock Star

3:05 -

B7. Un Jour Mon Prince Viendra

2:21 -

B8. On L'A Dans L'Baba

3:06

A pop star who turned his back to show business to become an independent artist, steered by the revolutionary ideas of his wife Jacqueline in 1960’s France; these are the outlines of Henri Salvador’s unusual musical career. It made him into a star then led him to entirely dissociate from the record industry, preferring to make music in his living room with his guitars. At 50, Salvador starts experimenting with synths and drum machine, multi-track recorders and altered voice collages. He takes up editing and mixing, and solitarily makes songs for young and old from his home in Paris’ Place Vendôme.

“Unfortunately, it’s not beautiful songs that make an amazing career. These are songs that will exist after I die.” (1969)

How can one even begin to tell the story of Salvador? Seventy years of music, a thousand of creations of all styles. He has known each and every genre and trend, appropriated some and invented yet new ones. Sometimes associated to ye-ye singers, he’s also known to have brought rock to France (in 1956, with Boris Vian). Yet he’s 26 years older than Johnny Hallyday. He’s 47 when Zorro est arrivé is released in 1964… and 83 at the release of Jardin d’hiver. Seen with today’s eyes it’s all very dizzying. You never know whether he’s young or old, or under which label to file him: jazzman, crooner, entertainer, composer, guitar player, children song singer…

As a kid he picks up the guitar without any theoretical basics and becomes so talented he plays with Django Reinhardt. He learns to sing and compose on his own. The 30s are the years of his training; the 40s of his emancipation within musical ensembles which are to see his talents flourish. He finds his public and perfects his tricks: laughter and seduction. In the 50s he rediscovers the songs of the islands where he grew up, revisits jazz, swing, blues and sings for children. It’s the years of his unforgettable “sweet song”, and his voice changes. His cheeky humour makes way for a multifaceted talent, he fills up venues, surrounds himself with serious lyricists and accumulates classics: Le blues du dentiste, Dans mon île, Syracuse.

“My wife has come to understand me so well that she can now think in my place. When she has an idea it’s, so to speak, my own idea!” (Télé Magazine, 1972)

Jacqueline shapes and emancipates him. When they marry in 1950, she’s a quiet and cultivated young lady who’s to progressively take charge of his career. She enforces her views and frantic pace. A spectator in the world of show business, Jacqueline realises that the artists, left out of professional conversations, often get cheated. Henri undoes the chains binding him to Philps, Vogue, Barclay, his editor, his manager and his impresario, and becomes independent. The Salvadors get to know the inner workings of production, edition, record pressing, distribution and promotion. They always have material to record a demo at hand. Their apartment is full of recorders: one at the bed end for the guitar, yet another in Henri’s office for the Steinway. He’s on all fronts; he accumulates hits, invents, mocks, adapts, and produces.

Place Vendôme sees the birth of the label Rigolo. Why Rigolo (French for “funny”)? “Because it’s funny”, he used to answer. Homemade clips are broadcasted in TV shows they self-produce: Salves d’Or (a play on words sounding like “Salvador” meaning “bursts of gold”) and Dimanche Salvador. Their approach turns out to be profitable. The Salvador couple enters the 70s with confidence.

At times, Henri takes out the cabriolet along with his colporteurs on record shop tours. Meanwhile Jacqueline is a formidable businesswoman. Disney threatens to sue the singer over his use of the name Zorro: she turns the situation to her advantage and cashes in on a Disney-Salvador contract. The decade will see them release five records: Les Aristochats (“The Aristocats”), Blanche-Neige (“Snow White”), Le petit Poucet (“Hop-o'-My-Thumb”), Robin des Bois (“Robin Hood”) and Pinocchio. Ever reinventing themselves, the Salvadors intend to do without studios, engineers, producers and musicians altogether.

“I started working with just a tiny recorder. Now I’ve gotten to sixteen tracks. I have electronic drums and my instruments. I can give the impression of a full orchestra. It’s amazing, I have as many musicians as I want at my disposal, at whichever time of day and night” (1972)

They install a high-end recording studio in their living room they nickname the PAM – referring to the name of their company, Productions Artistiques et Musicales. Louis Chedid remembers, “there was a huge mixer, custom made I believe, a 3M tape recorder. They must have had the very first drum machines, the ones that accompanied organs for example, inspired by the Ace Tone; they came with pre-recorded beats like 'samba' or 'biguine' [pressing two keys simultaneously you could combine them]. Plus there were quite a few guitars. What I do remember very well is his guitar playing. He was seen as an entertainer but, really, he was a virtuoso.”

Using his mixer and reels, Henri endlessly multiplies and harmonises his voice. Everything is done hastily though with care. He plays around with the offbeat sounds of the synths, has a blast with the drum machines. He uses all of the pre-recorded beats, loops the “fillers” to generate more beats, fiddles with the speeds, programs his own, sometimes goofy rhythms. This creative shift changes his musical groove. Salvador invented a mechanical jazz for himself, one that gathered its swing from the guitars and its energy from the vocals. He worked around his weakness on the bass with his strings and Moog keyboard. To get his public used to this new style, the PAM first produces a few singles’ B-sides – On n’est plus chez nous, which recounts the story of two scat-men interrupted by a passerby looking for Place de l’Opéra in Paris. Then an A-side: Ah ce qu’on est bien quand on est dans son bain, (which could be translated as “Oh how nice it feels to bathe”), which was recorded straight from the bathroom and became 1970’s Christmas hit. And finally the first self-released album: Les Aristochats, rewarded by the Charles Cros Academy in 1971. Many things are in Jacqueline’s hands: the lead, the books, and even the keys of the studio: at times Henri would get locked in to compose, let out only to work on his TV shows.

Under his contract with Disney, he’s required to produce family-friendly records. Along with his authors he creates songs about Uncle Scrooge, Sneezy and Mickey. He combines them to other, very peculiar, pieces: Les voisins (“The neighbours”), an old hater complains about the noise; Petit Lapin (“Little Bunny”), a city man advises a rodent not to settle in town; Voilactus, (from “voie lactée”, French for the Milky Way) an alien mocks our banking system; J’ai envie de Lucie, in which the narrator explains how he’s always longing for Lucie; Maman Papa, a spoiler for kids on how to hate theirs parents later on in life; but also Le temps des cons (“The time of the jerks”), a harsh commentary on French society.

“I make kids laugh. I love to belong to this audience, the most righteous and the most severe. If they like you, they tell you; if they don’t like you, they tell you, too.” (Télé-Star, 1977)

These LPs are also full of tender songs, dance floor baits and environmentalist vignettes - a hodgepodge less well regarded than his sixties period. And yet it’s a boisterous collection of gems, with a peculiar signature and many fresh ideas. Siffler en travaillant (“Whistle While You Work”) is a brilliant reinterpretation of one of Snow White’s theme song, which a young Salvador had already performed with Ray Ventura’s Orchestra in the 40s; Hello Mickey, a catchy, spirited ska; J’aime tes g’noux, a great cover of Shirly and Co’s Shame shame shame; on Un jour mon prince viendra, he makes a beat borrowed from Suicide and a Les Paul solo collide.

Meanwhile Rigolo also releases less family-oriented singles. After all, Salvador’s in for a bit of fun. He takes up eroticism, the financial crisis, and the negotiations between the US and Vietnam. He writes some luminous ballads such as Marjorie and catchy classics like Pauvre Jésus Christ. Some tracks are the result of unbridled experimentation, like Sex Man – particularly innovative – or Et des mandolines, an ode to cool eyeing on the side of Lucio Battisti. He makes the score of a messy film, L’explosion. The soundtrack was only released in Canada though it’s full of wonderful material like Thème du bateau or the depressing though dazzling Le bilan, written by his friend, the drummer Moustache.

Should he have kept recording in his living room beyond 1975, where would have Salvador ended up? Would he have been found to be one of the pioneers of rap or techno? In 1975 Jacqueline is diagnosed with a cancer. As she manages, decides and initiates everything, Rigolo starts idling. The year’s only release, Pinocchio, is finished in a rush and poorly distributed. The Salvadors accumulate medical consultations but the following year Jacqueline passes away. It’s the end of an era, the end of the home studio. Weary and beat, Henri doesn’t feel like playing in his empty house anymore. He lets all of their projects die out: the TV show, the label, the musical editions, the PAM. It’s a free-for-all; the labels and editors scramble at his door. He’s robbed and pressed for more Disney albums. Peter Pan is on the way, Bernard et Bianca (“The Rescuers”) and Mary Poppins should be next, but nothing comes out. His old impresario Marouani helps him back on his feet and takes him to the other side of the globe to drown his sorrows. Henri had never gotten on a plane before.

“He’s my man, my child, my baby and my islands’ memories. I’m his shadow and alter ego. I live for him.” (Jacqueline Salvador, 1973)

Back in line, he records Salvador 77 with a handful of producers. He slips in two oldies from his home-studio period: Rock star, a Johnny Hallyday parody made for their TV show at the time and L’amour, va, ça va, made in his crooner style. The latter is an outsider with its sloppy arrangements. The synth is so saturated on the record it seems the speakers might just blow up. In 1978, for RCA still, he records On l’a dans l’baba in the studio. It resembles a typical electronic track with a Vocoder – the beat though doesn’t emanate from a drum machine but from a flesh-and-blood drummer. Here again however the irony didn’t bother Salvador. And neither us – we included the song as the closing-track of our compilation.

In 1980, he handwrites “Si vous ne l’aimez pas, allez vous faire foutre” (literally, “If you don’t like it, go fuck yourselves”) on the sleeve of his latest album. We’ll never know whether it was meant for the journalists or his label. He records the same hits again, releases dull singles. All the same, he remains a great performer who can get the whole of Paris dancing, as well as a champion for the youth (Emilie Jolie, La petite sirène). The 90s may prove to be artistically poor, they are emotionally rich for Salvador: he meets his last wife, Catherine. Lifted and lit up once again, he makes his comeback in the 2000s with Chambre avec vue.

“In the 60s, the artists were getting ripped off with ridiculous rates. In the 80s, the lawyers got involved. The economy changed and non-recoverable advance payments emerged. Labels started financing artists so they wouldn’t end up doing like Salvador did.” (Louis Chedid)

Together with Jacqueline, Henri Salvador should’ve set an example for other artists: one of independence against an unfair and unyielding system. An inspiration not to end up enslaved by contracts signed too early, or to feed a bunch of comatose owners clenching onto millions of publishing rights. Be glad, music-consumer friends: tonight a pen-pusher will offer himself an entrecote thanks to the money you kindly invested in this compilation. Happy listening.

“Unfortunately, it’s not beautiful songs that make an amazing career. These are songs that will exist after I die.” (1969)

How can one even begin to tell the story of Salvador? Seventy years of music, a thousand of creations of all styles. He has known each and every genre and trend, appropriated some and invented yet new ones. Sometimes associated to ye-ye singers, he’s also known to have brought rock to France (in 1956, with Boris Vian). Yet he’s 26 years older than Johnny Hallyday. He’s 47 when Zorro est arrivé is released in 1964… and 83 at the release of Jardin d’hiver. Seen with today’s eyes it’s all very dizzying. You never know whether he’s young or old, or under which label to file him: jazzman, crooner, entertainer, composer, guitar player, children song singer…

As a kid he picks up the guitar without any theoretical basics and becomes so talented he plays with Django Reinhardt. He learns to sing and compose on his own. The 30s are the years of his training; the 40s of his emancipation within musical ensembles which are to see his talents flourish. He finds his public and perfects his tricks: laughter and seduction. In the 50s he rediscovers the songs of the islands where he grew up, revisits jazz, swing, blues and sings for children. It’s the years of his unforgettable “sweet song”, and his voice changes. His cheeky humour makes way for a multifaceted talent, he fills up venues, surrounds himself with serious lyricists and accumulates classics: Le blues du dentiste, Dans mon île, Syracuse.

“My wife has come to understand me so well that she can now think in my place. When she has an idea it’s, so to speak, my own idea!” (Télé Magazine, 1972)

Jacqueline shapes and emancipates him. When they marry in 1950, she’s a quiet and cultivated young lady who’s to progressively take charge of his career. She enforces her views and frantic pace. A spectator in the world of show business, Jacqueline realises that the artists, left out of professional conversations, often get cheated. Henri undoes the chains binding him to Philps, Vogue, Barclay, his editor, his manager and his impresario, and becomes independent. The Salvadors get to know the inner workings of production, edition, record pressing, distribution and promotion. They always have material to record a demo at hand. Their apartment is full of recorders: one at the bed end for the guitar, yet another in Henri’s office for the Steinway. He’s on all fronts; he accumulates hits, invents, mocks, adapts, and produces.

Place Vendôme sees the birth of the label Rigolo. Why Rigolo (French for “funny”)? “Because it’s funny”, he used to answer. Homemade clips are broadcasted in TV shows they self-produce: Salves d’Or (a play on words sounding like “Salvador” meaning “bursts of gold”) and Dimanche Salvador. Their approach turns out to be profitable. The Salvador couple enters the 70s with confidence.

At times, Henri takes out the cabriolet along with his colporteurs on record shop tours. Meanwhile Jacqueline is a formidable businesswoman. Disney threatens to sue the singer over his use of the name Zorro: she turns the situation to her advantage and cashes in on a Disney-Salvador contract. The decade will see them release five records: Les Aristochats (“The Aristocats”), Blanche-Neige (“Snow White”), Le petit Poucet (“Hop-o'-My-Thumb”), Robin des Bois (“Robin Hood”) and Pinocchio. Ever reinventing themselves, the Salvadors intend to do without studios, engineers, producers and musicians altogether.

“I started working with just a tiny recorder. Now I’ve gotten to sixteen tracks. I have electronic drums and my instruments. I can give the impression of a full orchestra. It’s amazing, I have as many musicians as I want at my disposal, at whichever time of day and night” (1972)

They install a high-end recording studio in their living room they nickname the PAM – referring to the name of their company, Productions Artistiques et Musicales. Louis Chedid remembers, “there was a huge mixer, custom made I believe, a 3M tape recorder. They must have had the very first drum machines, the ones that accompanied organs for example, inspired by the Ace Tone; they came with pre-recorded beats like 'samba' or 'biguine' [pressing two keys simultaneously you could combine them]. Plus there were quite a few guitars. What I do remember very well is his guitar playing. He was seen as an entertainer but, really, he was a virtuoso.”

Using his mixer and reels, Henri endlessly multiplies and harmonises his voice. Everything is done hastily though with care. He plays around with the offbeat sounds of the synths, has a blast with the drum machines. He uses all of the pre-recorded beats, loops the “fillers” to generate more beats, fiddles with the speeds, programs his own, sometimes goofy rhythms. This creative shift changes his musical groove. Salvador invented a mechanical jazz for himself, one that gathered its swing from the guitars and its energy from the vocals. He worked around his weakness on the bass with his strings and Moog keyboard. To get his public used to this new style, the PAM first produces a few singles’ B-sides – On n’est plus chez nous, which recounts the story of two scat-men interrupted by a passerby looking for Place de l’Opéra in Paris. Then an A-side: Ah ce qu’on est bien quand on est dans son bain, (which could be translated as “Oh how nice it feels to bathe”), which was recorded straight from the bathroom and became 1970’s Christmas hit. And finally the first self-released album: Les Aristochats, rewarded by the Charles Cros Academy in 1971. Many things are in Jacqueline’s hands: the lead, the books, and even the keys of the studio: at times Henri would get locked in to compose, let out only to work on his TV shows.

Under his contract with Disney, he’s required to produce family-friendly records. Along with his authors he creates songs about Uncle Scrooge, Sneezy and Mickey. He combines them to other, very peculiar, pieces: Les voisins (“The neighbours”), an old hater complains about the noise; Petit Lapin (“Little Bunny”), a city man advises a rodent not to settle in town; Voilactus, (from “voie lactée”, French for the Milky Way) an alien mocks our banking system; J’ai envie de Lucie, in which the narrator explains how he’s always longing for Lucie; Maman Papa, a spoiler for kids on how to hate theirs parents later on in life; but also Le temps des cons (“The time of the jerks”), a harsh commentary on French society.

“I make kids laugh. I love to belong to this audience, the most righteous and the most severe. If they like you, they tell you; if they don’t like you, they tell you, too.” (Télé-Star, 1977)

These LPs are also full of tender songs, dance floor baits and environmentalist vignettes - a hodgepodge less well regarded than his sixties period. And yet it’s a boisterous collection of gems, with a peculiar signature and many fresh ideas. Siffler en travaillant (“Whistle While You Work”) is a brilliant reinterpretation of one of Snow White’s theme song, which a young Salvador had already performed with Ray Ventura’s Orchestra in the 40s; Hello Mickey, a catchy, spirited ska; J’aime tes g’noux, a great cover of Shirly and Co’s Shame shame shame; on Un jour mon prince viendra, he makes a beat borrowed from Suicide and a Les Paul solo collide.

Meanwhile Rigolo also releases less family-oriented singles. After all, Salvador’s in for a bit of fun. He takes up eroticism, the financial crisis, and the negotiations between the US and Vietnam. He writes some luminous ballads such as Marjorie and catchy classics like Pauvre Jésus Christ. Some tracks are the result of unbridled experimentation, like Sex Man – particularly innovative – or Et des mandolines, an ode to cool eyeing on the side of Lucio Battisti. He makes the score of a messy film, L’explosion. The soundtrack was only released in Canada though it’s full of wonderful material like Thème du bateau or the depressing though dazzling Le bilan, written by his friend, the drummer Moustache.

Should he have kept recording in his living room beyond 1975, where would have Salvador ended up? Would he have been found to be one of the pioneers of rap or techno? In 1975 Jacqueline is diagnosed with a cancer. As she manages, decides and initiates everything, Rigolo starts idling. The year’s only release, Pinocchio, is finished in a rush and poorly distributed. The Salvadors accumulate medical consultations but the following year Jacqueline passes away. It’s the end of an era, the end of the home studio. Weary and beat, Henri doesn’t feel like playing in his empty house anymore. He lets all of their projects die out: the TV show, the label, the musical editions, the PAM. It’s a free-for-all; the labels and editors scramble at his door. He’s robbed and pressed for more Disney albums. Peter Pan is on the way, Bernard et Bianca (“The Rescuers”) and Mary Poppins should be next, but nothing comes out. His old impresario Marouani helps him back on his feet and takes him to the other side of the globe to drown his sorrows. Henri had never gotten on a plane before.

“He’s my man, my child, my baby and my islands’ memories. I’m his shadow and alter ego. I live for him.” (Jacqueline Salvador, 1973)

Back in line, he records Salvador 77 with a handful of producers. He slips in two oldies from his home-studio period: Rock star, a Johnny Hallyday parody made for their TV show at the time and L’amour, va, ça va, made in his crooner style. The latter is an outsider with its sloppy arrangements. The synth is so saturated on the record it seems the speakers might just blow up. In 1978, for RCA still, he records On l’a dans l’baba in the studio. It resembles a typical electronic track with a Vocoder – the beat though doesn’t emanate from a drum machine but from a flesh-and-blood drummer. Here again however the irony didn’t bother Salvador. And neither us – we included the song as the closing-track of our compilation.

In 1980, he handwrites “Si vous ne l’aimez pas, allez vous faire foutre” (literally, “If you don’t like it, go fuck yourselves”) on the sleeve of his latest album. We’ll never know whether it was meant for the journalists or his label. He records the same hits again, releases dull singles. All the same, he remains a great performer who can get the whole of Paris dancing, as well as a champion for the youth (Emilie Jolie, La petite sirène). The 90s may prove to be artistically poor, they are emotionally rich for Salvador: he meets his last wife, Catherine. Lifted and lit up once again, he makes his comeback in the 2000s with Chambre avec vue.

“In the 60s, the artists were getting ripped off with ridiculous rates. In the 80s, the lawyers got involved. The economy changed and non-recoverable advance payments emerged. Labels started financing artists so they wouldn’t end up doing like Salvador did.” (Louis Chedid)

Together with Jacqueline, Henri Salvador should’ve set an example for other artists: one of independence against an unfair and unyielding system. An inspiration not to end up enslaved by contracts signed too early, or to feed a bunch of comatose owners clenching onto millions of publishing rights. Be glad, music-consumer friends: tonight a pen-pusher will offer himself an entrecote thanks to the money you kindly invested in this compilation. Happy listening.